The Backyard Winter Bird Survey Report: 2025

Dr. Pamela Hunt, Senior Conservation Biologist

Who still remembers February 2025?

The Backyard Winter Bird Survey (BWBS) took place at the start of an unusually cold stretch that lasted into March. In Concord, the average temperature in early February was five degrees below the long-term average, making the winter overall two degrees colder than normal—a sharp contrast to the recent trend of warmer winters. Many participants reported temperatures around ten degrees on Saturday morning of the survey, with Sunday feeling almost balmy as the thermometer climbed toward freezing. The season was also drier than usual, which may surprise some given the wet spring that followed. Lower snowfall was a big factor, although there was a significant storm across much of the state the very night of the survey.

Record Number of Observers!

While it’s always hard to know how much weather affects bird numbers, one factor stood out clearly in 2025: the record number of participants. A total of 1,953 people took part—nearly 300 more than the previous high of 1,678 set in 2021.

With more eyes on the birds, it’s no surprise that many feeder favorites also reached record totals, including Red-bellied and Downy Woodpeckers, Tufted Titmouse, Carolina Wren, Eastern Bluebird, House Sparrow, House Finch, and Northern Cardinal. This year’s report will focus more on “adjusted” counts (birds per observer) to account for the increase in participants. A full table of totals is included at the end of the report.

Three Standouts: Carolina Wrens, Red-bellied Woodpeckers, & Eastern Bluebirds

Three of these record-breaking species also set new highs in adjusted counts, showing that their increases weren’t just a result of more observers. The standout here is Carolina Wren, which surged above 1,000 for the first time. Some of this increase might be due to better documentation of this species from areas where it’s less likely, but as I’ve been saying for years these feisty wrens are only going to get more common.

Carolina Wren by Caitlin McMonagle on her 2025 BWBS.

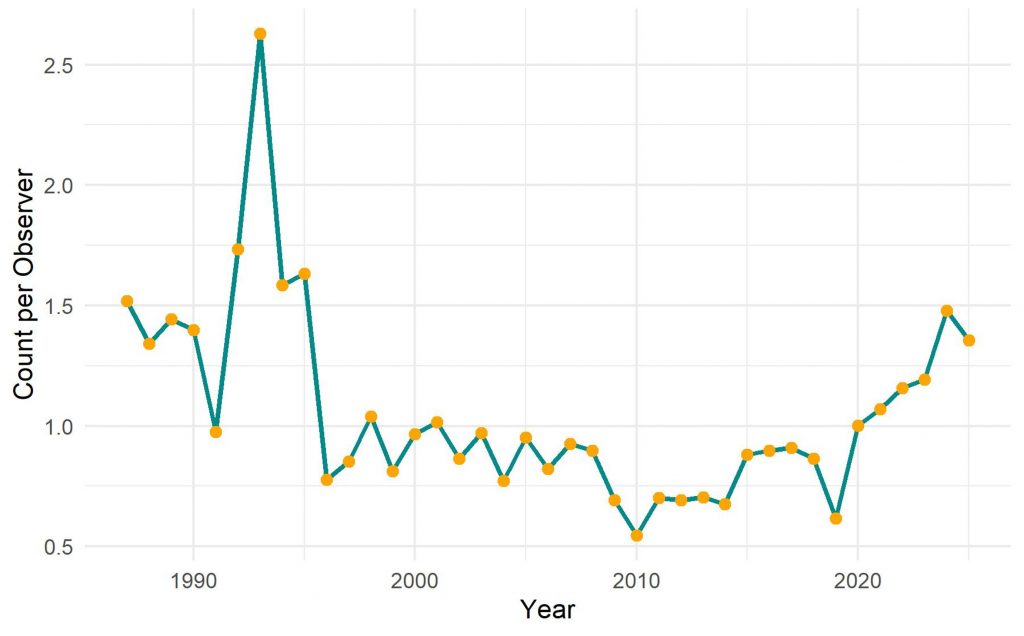

Average number of Carolina Wrens counted per observer (1987-2025) on the Backyard Winter Bird Survey.

Red-bellied Woodpeckers are another species that has expanded its range into New Hampshire and are increasing. It should come as no surprise that they also hit a record high of 1,389. The final standout here is another perennial favorite: the Eastern Bluebird, which is closing in on 5,000 individuals counted (2.5 per observer).

Average number of Eastern Bluebirds counted per observer (1987-2025) on the Backyard Winter Bird Survey.

House Finch History

House Finches tell a longer story. As I’ve reported here in the past, this non-native species was first introduced in New York City in 1939. It spread quickly in all directions, reaching New Hampshire in 1967. Numbers continued to increase into the early 1990s, but in 1994 a conjunctivitis outbreak started killing finches around Washington DC. The disease spread rapidly, reaching New Hampshire by 1996.

Within three years it had reduced House Finch populations in the eastern US by more than half. Numbers remained low for over twenty years but have started trending upward again since 2019. This recovery may represent the eastern population gaining a greater level of immunity to the bacterium that causes conjunctivitis.

Average number of House Finch counted per observer (1987-2025) on the Backyard Winter Bird Survey.

Half-hardies Continue to Rise

Just as Red-bellied Woodpeckers and Carolina Wrens have become a perennial topic in this summary, discussion of “half-hardies” is only going to become more frequent. For the uninitiated, these are species that typically spend the winter south of New England but linger in the north when weather and/or food supplies permit it. In other words, they are more likely to survive a New Hampshire winter than long-distance migrants like most flycatchers, swallows, and warblers, but less adapted than more typical year-round residents like woodpeckers and chickadees. Hence the term “half-hardy.”

Northern Flickers are another half-hardy species we are seeing more of.

Lots of half-hardies will frequent feeders when they find themselves out of their element and thus get found by participants on the Backyard Winter Bird Survey. In 2024’s summary, I reported on new high counts for this group overall, and individual highs for several species (e.g., Pine Warbler and Eastern Towhee).

In 2025, we had one more Pine Warbler, than last year, 13 individuals.

Thank you to everyone who sent in photos to confirm this unusual species in winter. Photo by Jill Arabas.

Despite the colder-than-average winter of 2024-25 half-hardies again set records, with woodpeckers leading the charge. Our total of 42 Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers more than quintupled the previous record, a pattern that was seen in other data sets last winter. For example, I knew of at least five sapsuckers in Concord alone, whereas the Merrimack County Backyard Winter Bird Survey total for 2025 was “only” 11 (itself higher than the previous statewide high!). Hermit Thrushes also put in an exceptional showing, including many photographed by survey participants.

Photo by Fran Keenan on her 2025 BWBS

The stars of 2024, Eastern Towhee and Pine Warbler, tied their previous record or beat it by one, respectively. It seems likely that that this group of birds, like Carolina Wrens before them, is gradually becoming an expected component of our winter avifauna.

Backyard Raptors

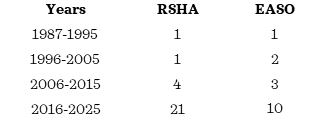

With the exception of Cooper’s Hawks, birds of prey don’t get a lot of attention in the Backyard Winter Bird Survey summary, but 2025 saw the continuation of some increasing trends. Leading the way was Red-shouldered Hawk, which set a new record with seven. Looking at the data overall, the number of records of this species (it could be considered another half-hardy) has skyrocketed with warmer winters, as shown in the table below. The same pattern is seen in one of our smallest raptors, the Eastern Screech-Owl. Does this mean the owl is stealthily increasing in New Hampshire, are more observers listening at night, or both?

Table 1. Numbers of Red-shouldered Hawks (RSHA) and Eastern Screech-Owls (EASO) by decade on the Backyard Winter Bird Survey.

A rare “Oregon” Dark-eyed Junco photographed by Jill Arabas on the 2025 Backyard Winter Bird Survey.

Not Everyone Had a Banner Year

Not every species had a banner year. The big “losers” in 2025 were the winter finches, with very few of these northern wanderers moving south into the Granite State. Evening Grosbeaks, were more common than in 2024 but certainly not widespread. Pine Grosbeaks, crossbills, and Redpolls were rare or absent. Of the other irruptive species, Bohemian Waxwings failed to appear entirely while Cedars were very hard to find anywhere. One of my other predictions was that Red-breasted Nuthatch would appear in numbers, and while there were more than in 2024, most were in the northern part of the state and their movement was underwhelming in the south.

Mourning Doves continue a slow decline based on adjusted data. The same is true for Black-capped Chickadees, which despite a slight uptick from 2024 are still half as common as they were 40 years ago (per observer).

Backyard Winter Bird Survey Rarities

Of course, there were also rarities. One new species was added to the Backyard Winter Bird Survey rolls in 2025: a Double-crested Cormorant in Portsmouth Harbor. With winters warming, this is another species becoming more common in winter along the coast. Gone are the days when one could assume any cormorant seen in New Hampshire from December to February was a Great Cormorant.

Another survey first was an “Audubon’s” Warbler in Hanover. This is the western subspecies of our familiar Yellow-rumped Warbler. It is most easily identified by its plainer face and yellow throat. Also visiting from the west was another unusual subspecies, an “Oregon” Junco in Hollis. Both these birds were present for most of the winter, no doubt providing a bit of extra excitement on cold dreary days.

Wrapping up the rarity list are orioles, which seem to be increasing in frequency like screech-owls. Of the eight Baltimore Orioles ever reported on the Backyard Winter Bird Survey, all but one have been in the last 20 years. This year’s bird was a female in Exeter.

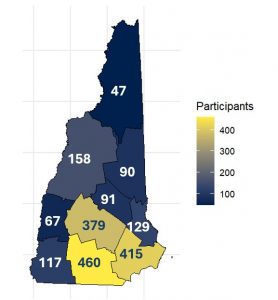

Participation by County

We were thrilled to have a record number of participants, 1953! Thank you for all who joined in, especially our new survey participants!

2025 Species Totals

Species at participants’ backyards on February 8 & 9, 2025.

Species with record high totals (or ties) are in bold.

New species for the Survey are denoted by an *

- Canada Goose: 463

- Mallard: 561

- American Black Duck: 7

- Bufflehead: 10

- Common Goldeneye: 21

- Goldeneye sp.: 4

- Hooded Merganser: 13

- Common Merganser: 33

- Red-breasted Merganser: 2

- Duck sp.: 119

- Ruffed Grouse: 4

- Wild Turkey: 2,814

- Rock Pigeon: 462

- Mourning Dove: 7,633

- Ring-billed Gull: 4

- Herring Gull: 18

- Gull sp.: 20

- Common Loon: 1

- Double-crested Cormorant: 1*

- Turkey Vulture: 20

- Vulture sp.: 2

- Northern Harrier: 1

- Sharp-shinned Hawk: 32

- Cooper’s Hawk: 50

- Cooper’s/Sharp-shinned: 6

- Bald Eagle: 42

- Eagle sp.: 5

- Red-shouldered Hawk: 7

- Red-tailed Hawk: 84

- Hawk sp.: 32

- Eastern Screech-Owl: 2

- Great Horned Owl: 6

- Barred Owl: 39

- Northern Saw-whet Owl: 1

- Owl sp.: 1

- Belted Kingfisher: 1

- Yellow-bellied Sapsucker: 42

- Red-bellied Woodpecker: 1,389

- Downy Woodpecker: 2,893

- Hairy Woodpecker: 1,638

- Pileated Woodpecker: 206

- Northern Flicker: 78

- Woodpecker sp.: 4

- Merlin: 2

- Peregrine Falcon: 1

- Canada Jay: 5

- Blue Jay: 7,138

- American Crow: 2,445

- Fish Crow: 1

- Common Raven: 205

- Black-capped Chickadee: 8,490

- Tufted Titmouse: 5,211

- Golden-crowned Kinglet: 7

- Red-breasted Nuthatch: 734

- White-breasted Nuthatch: 2,712

- Brown Creeper: 144

- Winter Wren: 1

-

Carolina Wren: 1,124

-

European Starling: 3,287

-

Gray Catbird: 1

-

Northern Mockingbird: 114

-

Eastern Bluebird: 4,731

-

Hermit Thrush: 10

-

American Robin: 2,588

-

Cedar Waxwing: 139

-

House Sparrow: 3,283

-

Evening Grosbeak: 730

-

House Finch: 2,647

-

Purple Finch: 220

-

Redpoll: 33

-

Pine Siskin: 455

-

American Goldfinch: 9,160

-

Snow Bunting: 17

-

Chipping Sparrow: 3

-

American Tree Sparrow: 594

-

Fox Sparrow: 6

-

Dark-eyed Junco: 10,490

-

“Oregon” Junco: 1

-

White-throated Sparrow: 568

-

Song Sparrow: 98

-

Sparrow sp.: 84

-

Eastern Towhee: 5

-

Baltimore Oriole 1

-

Red-winged Blackbird: 48

-

Brown-headed Cowbird: 6

-

Common Grackle: 93

-

Pine Warbler: 13

-

Yellow-rumped (Audubon’s) Warbler: 1*

-

Northern Cardinal: 3,710

Total Confirmed Bird Species: 78

- Eastern Chipmunk: 104

- Red Squirrel: 657

- Gray Squirrel: 4,285

Interested in learning more?

Check out our archive of past Backyard Winter Bird Survey Reports.